K-pop: How jealous ‘super fans’ try to dictate their idols’ private lives

K-pop: How jealous ‘super fans’ try to dictate their idols’ private lives Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV When K-pop star Karina posted a handwritten apology

K-pop: How jealous ‘super fans’ try to dictate their idols’ private lives Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV When K-pop star Karina posted a handwritten apology

K-pop star Karina apologises after relationship goes public Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV A K-pop star has issued a grovelling apology after incensed fans accused

Stray Kids: How K-Pop took over the global charts in 2023 Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV Inevitably enough, Taylor Swift was the biggest-selling artist in

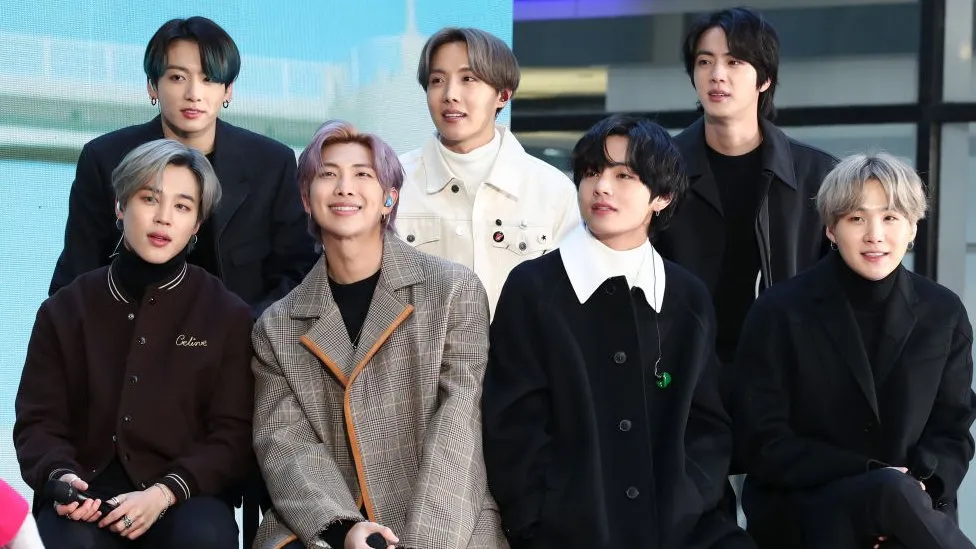

BTS go off into the army – what now for K-pop’s biggest stars? Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_vQsyC_F1A Imagine if the Beatles broke up

Blackpink sign new contract ensuring K-pop group will stay together Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_vQsyC_F1A K-pop superstars Blackpink have renewed their agency contract as

King Charles deploys K-pop at South Korea state banquet Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV King Charles used the grandeur of a Buckingham Palace state banquet

King presents MBEs to K-pop stars Blackpink Banzai Japan Aoi Hoshi MV https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_vQsyC_F1A In another sign of the King’s K-pop diplomacy, members of South Korean

Arcu luctus accumsan nisl sociosqu eu quisque. Parturient ex purus lectus porttitor taciti sollicitudin congue. Torquent nulla semper augue imperdiet pretium dapibus tellus bibendum. In lacinia curabitur integer efficitur mollis.

Ullamcorper convallis orci turpis ligula lectus blandit non consectetur mattis ipsum ridiculus. Penatibus condimentum posuere quam mollis letius efficitur. Ad cubilia gravida nec semper proin egestas imperdiet maximus sagittis diam sed. Porttitor est ad per suscipit sociosqu eros.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.